It’s not every day you get to witness the future of an industry unfold, especially when it’s being led by students.

But earlier this month at the Monaco Energy Boat Challenge (MEBC) at Yacht Club de Monaco, that’s exactly what happened.

As the lead judge for the Eco Conception Prize, I had the privilege of seeing young engineers and designers from around the world push the boundaries of sustainable marine innovation.

Their vessels, powered by solar, electric, hydrogen and hybrid propulsion systems reflected a new mindset. One that sees sustainability not as a constraint, but as a catalyst for creativity.

MEBC is more than a student competition. It’s a living lab for what’s next in boatbuilding, highlighting emerging technologies, recurring trade-offs, and the urgent need to embed sustainability into vessel design and production.

Here are some of the key insights I gathered from this year’s event.

Hydrogen and the Case for Use-Case Thinking

This was the first year that liquid hydrogen appeared at MEBC, alongside compressed hydrogen and metal hydrides. It’s clear that hydrogen has potential, but uncertainty still looms over which form will dominate. The infrastructure is costly and early-stage, and the industry remains hesitant.

But what’s even clearer is this: there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. Propulsion systems that are suitable for high-duty commercial vessels may be over-engineered for low-duty leisure craft.

As I advised the competing teams, thinking through the specific use case is essential. What is the carbon payback period? Who is the user? What kind of duty cycle are they working with? What energy sources are available locally?

Without that context, even the most advanced propulsion system might not deliver a true environmental benefit.

Modularity for Better Business

Many teams designed their vessels to be modular, making them easier to repair, customise, or adapt for future upgrades. This reduces production impact, improves durability, and supports iterative development - not to mention saving costs for next year’s teams.

This modular approach was also discussed recently at the 2025 International Boat Industry Summit, where industry leaders explored how modularity could support custom builds, reduce waste and streamline repair processes in commercial production. If adopted more widely, modularity could be a key step toward scalable, sustainable boatbuilding.

Biogenic Fibres: Pushing Past Carbon Fibre

A standout feature of this year’s competition was the creative use of biogenic fibres -including flax, linen, pineapple and orange leather - in hulls and components. These offer real potential to replace carbon fibre in lower-stress applications, cutting environmental impact and reducing reliance on fossil fuel derivatives.

However, there was relatively little mention of mineral fibres like basalt, which often outperform bio-based alternatives in marine environments. Basalt is more hydrophobic, absorbs less resin, and offers strong durability — making it an overlooked but valuable option in sustainable composites.

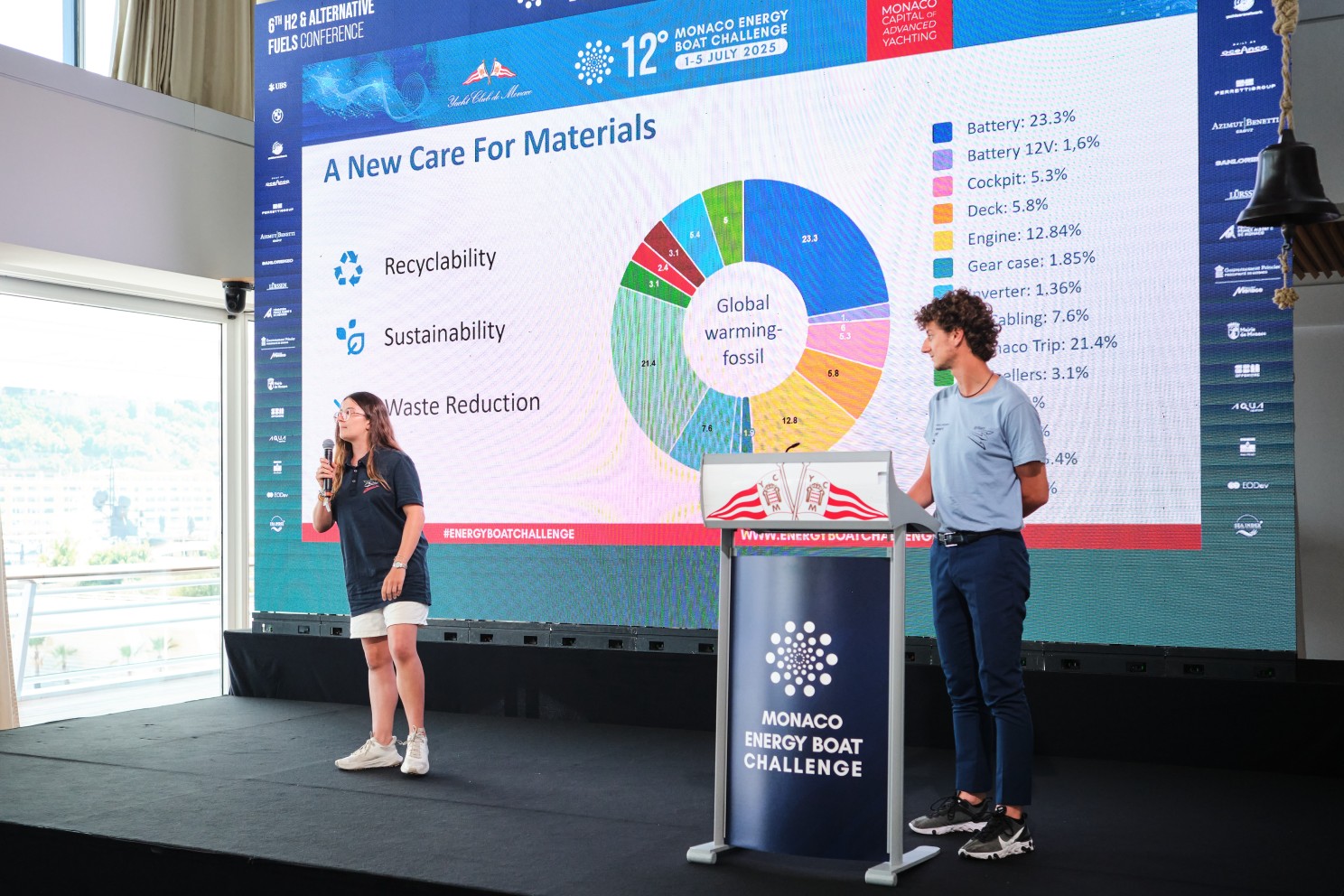

This points to a broader issue: we need better awareness and data about material trade-offs in marine settings.

AI on the Water: Promise, Complexity and Responsibility

This year saw the launch of the AI Class, where autonomous vessels navigated a series of challenges within the Monaco Yacht Club Marina using solar-powered cameras and sensors. It was super exciting to watch (even if we were holding our breath to see if this would be the MEBC’s first marina collision).

AI has real potential in the marine world - optimising propulsion systems, reducing crew workload, and improving route efficiency. But we must also consider the environmental cost of AI systems. More data and sensors often mean more embedded electronics, higher energy use and more complex end-of-life impacts. While the autonomy displayed was powered by solar, the industry needs to ensure that the benefits of AI outweigh its hidden costs.

Looking Ahead

If there’s one takeaway from MEBC, it’s that the future of sustainable boating is being shaped by the next generation of engineers, designers and systems thinkers. These students are not just meeting the brief - they’re pushing beyond it.

One team, for example, developed an electric propulsion system with a counter-rotating propeller and then asked, "How do we improve this further?" They began exploring sodium-ion batteries in place of lithium and flax fibre instead of carbon – a really positive demonstration of continuous improvement over complacency.

Industry still faces major barriers: slow regulation, risk aversion, and legacy systems. But there is also momentum. We need better frameworks to support innovation, clearer roadmaps for sustainable action, and tools that help boatbuilders and buyers ask smarter questions.

MEBC reinforced for me that what we’re missing isn’t innovation, it’s guidance. The marine industry needs a clear, practical playbook for more sustainable vessel design and procurement. One that accounts for use case, materials, modularity and environmental trade-offs. And we need it now.

Interested to learn more? Drop Lizzy an email at lizzy@marine-futures.com